How will remote workers choose to live in a new era of flexible work?

Part 3 of Donuts & Megaregions: The New Economic Geography of Remote Work

This is part 3 of my 4-part series on remote work and its impact on the housing market. Part 1 can be found here, and part 2 can be found here.

For all but the wealthiest households, raising a family in a big city like NYC or SF can be a grind. Between housing and childcare, a household with two high-income earners can quickly start to feel not so well off. Yes, yes - first world problems and all. But still, for a couple who’s in that situation, the cost-of-living challenge feels pretty important.

Then there are the challenges associated with ensuring your children receive a high-quality education. Then throw in the so-called “quality of life issues” that plague many of our urban communities, and the calculus for many young families can quickly shift to looking outside the city for the next phase of their life.

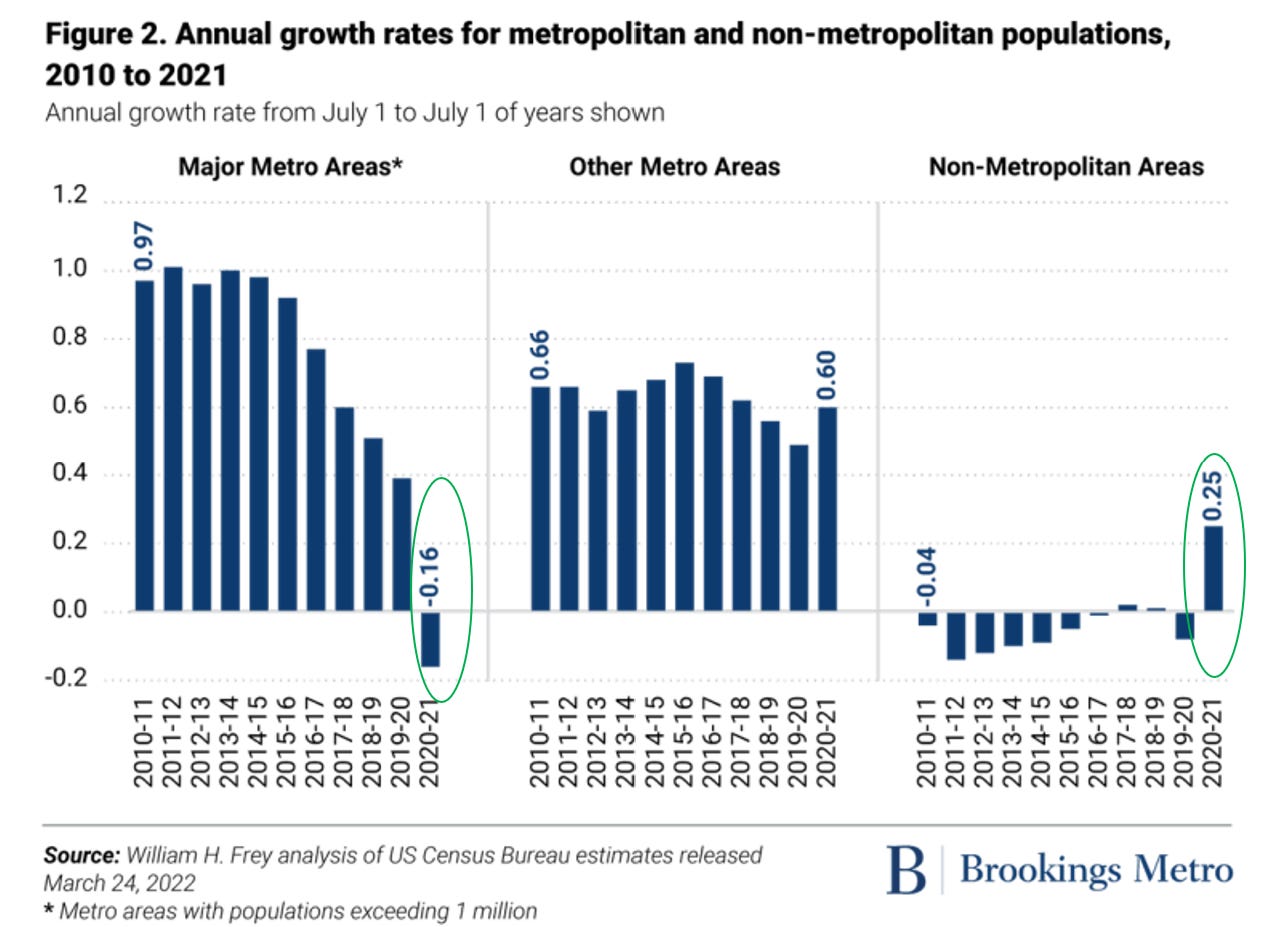

Our urban cores were temporarily hollowed out during the acute pandemic period as the amenities that made city life “worth it” were no longer available. This resulted in a rapid acceleration of trends that were already in place before the pandemic. Basically, pandemic-driven shutdown policies accelerated a lot of moves to the suburbs that were going to happen anyway.

Most cities have bounced back nicely from that time and will continue to grow. Some haven’t (looking at you, San Francisco). But it’s pretty well documented that our urban cores lost population during the pandemic.

An interesting trend here is that a lot of the pandemic-era domestic migration was from major metros to smaller sized markets and even rural regions. One of the new trends to keep an eye on is the decision by many knowledge workers, especially those with families, to move further out into rural or semi-rural areas where there’s more space, more access to nature, and a lifestyle that’s complementary to occasionally spending time in the city for work or for pleasure.

In other words, many remote workers aren’t choosing to move from one major metro to another major metro; they’re choosing to move from cities to less populated, less expensive areas altogether, and then maybe shuttling into the city for work events or social functions or flying to other cities for the same. These remote workers are city quitters or super commuters.

Another major cohort of knowledge workers has elected to become digital nomads, shuttling from city to city, place to place and working from wherever they want to be.

If these trends hold up - digital nomadism, city quitters, super commuters - we could be seeing the emergence of an information worker diaspora. These workers are choosing to live more diverse and mobile lifestyles that capitalize on their newfound flexibility, and this is resulting in a geographic redistribution of talent and innovation.

Over the last 50 years or so, the story of the US’s economic geography as it relates to innovation and talent has had two main characters: migration and agglomeration. Innovation has clustered or agglomerated around a handful of metro hubs, and talent has migrated into those metro hubs from outside of them. All this happens with self-reinforcing dynamics that look like winner-take-all markets, which led to the rise of “superstar” cities.

We’ve now seen some reverse migration as talent seeps out of these urban innovation hubs, because those workers can find a better quality of life elsewhere while keeping the jobs that, historically speaking, would have only been available in San Francisco, Boston, or New York.

For younger workers, however, especially those just out of college, the draw of city life is hard to beat. So the young tech worker who wants to work at the next powerhouse tech company may still decamp for San Francisco, and the aspiring biotech entrepreneur may still head out to Boston. For these folks, having many older workers leave the cities could be great news, since it means they’ll be competing with fewer people for renting apartments.

There’s no doubt that the remote work-driven “death of cities” has been greatly exaggerated. But at the same time, the rise of remote work means both workers and firms will be able to settle into less expensive regions with little to no tradeoff in terms of job opportunities for workers or talent opportunities for firms. That’s a big change.

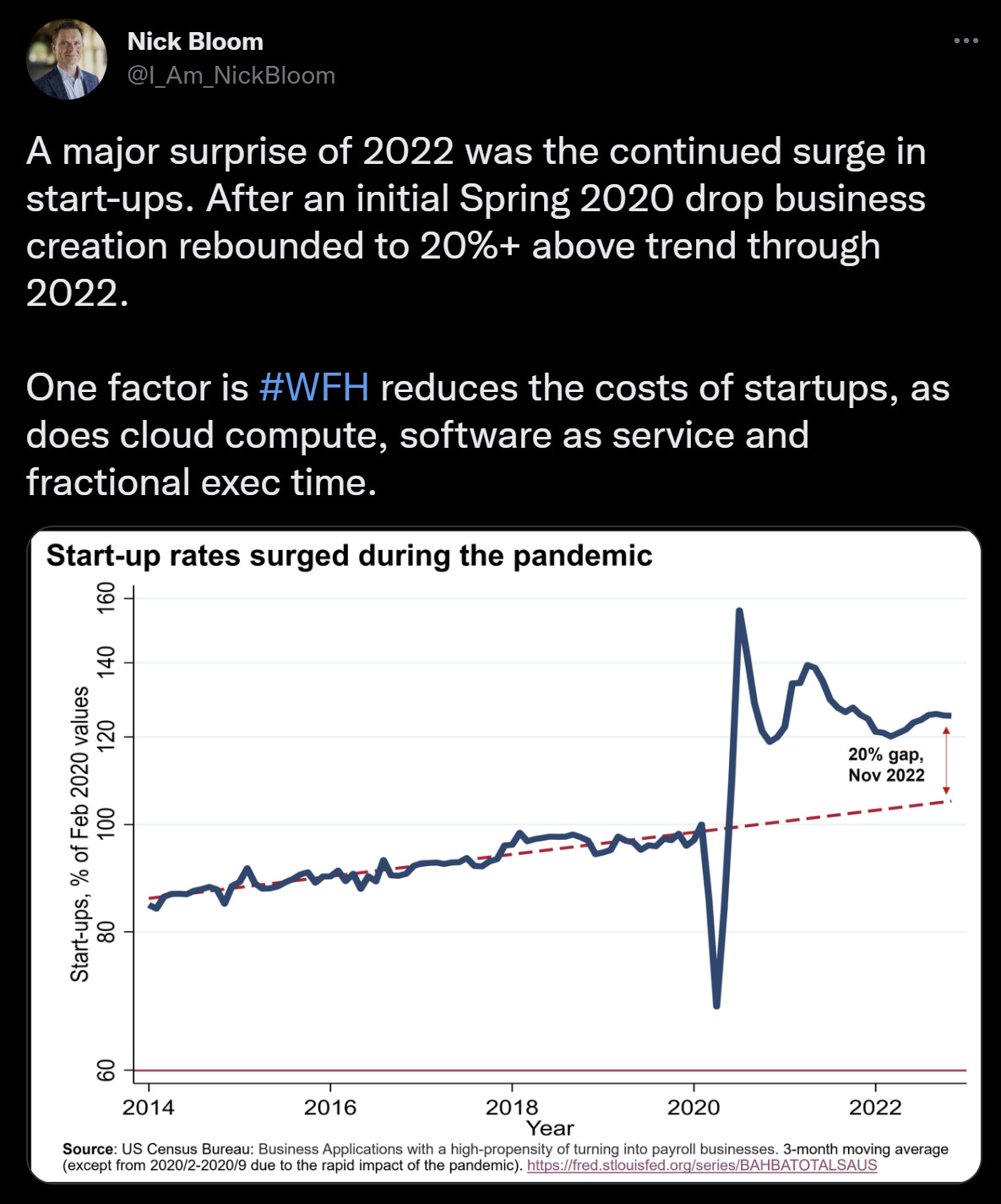

Another big change we’re seeing is that a lot more startups seem to be getting formed today than before the pandemic. The availability of remote work might help explain why we’ve seen an explosion in startups over the last couple of years running well above pre-pandemic trends.

Perhaps instead of keeping their big city job while living in a non-big city market, some workers are using the lower cost of living they now enjoy as leverage to start new companies.

With digital collaboration tools like Slack and Zoom, modular as-a-service technical infrastructure, and cloud-based compute power, the barriers to entry from a cost and technology perspective for launching a startup have never been lower.

It could be the case that remote work has conquered important social and economic barriers to more startup founders taking the leap. Remote work might now supercharge the production of new founders.

Remote work makes it much easier for one spouse to drop out of the workforce to launch a startup while the other spouse’s income is sufficient to cover household expenses comfortably. This might be especially true if one couple generates an income from a “big city” job that’s now being done in a lower cost of living market.

The rise of the information worker diaspora is, in the words of economist Enrico Moretti, akin to “a national seed-planting experiment that has the potential to grow new industrial clusters.” We may be on the verge of another industrial revolution that happens in the cloud - one that’s happening everywhere and nowhere in particular at the same time. Let a million innovation mini-clusters bloom.