Donuts & Megaregions: What’s the impact of remote work on the housing market?

Part 1: Introduction

The US has a unique economic geography relative to other developed countries. Since metropolitan areas in the US developed in the age of the automobile, its cities tend to be less dense and walkable than those of Western Europe. The sprawl and homogeneity of suburban America dominate America’s landscape. Like it or not (and as you can probably tell, I don’t particularly), the US is a suburban nation, and that’s probably never going to change.

It’s easy to understand why.

The speed and efficiency of commuting by car was hard to beat for American workers ordering their lives in the 20th Century. The single family home within commuting distance of an office defined the pattern of American economic and family life. In an era of manufacturing and managerial capitalism, this pattern applied to a broad cross-section of American workers, whether it was the blue collar worker commuting to the plant or the white collar worker commuting to corporate HQ.

This car-centric development pattern was accelerated as a result of white flight from the cities and was then codified through exclusionary local zoning laws. As local policymakers sought to maintain a low-density housing model, they enacted inflexible land use regulations, which were also instituted for more unsavory purposes.

The low density, car-centric model caused population growth to gradually spill outward from urban to suburban to exurban rings around a metro core.

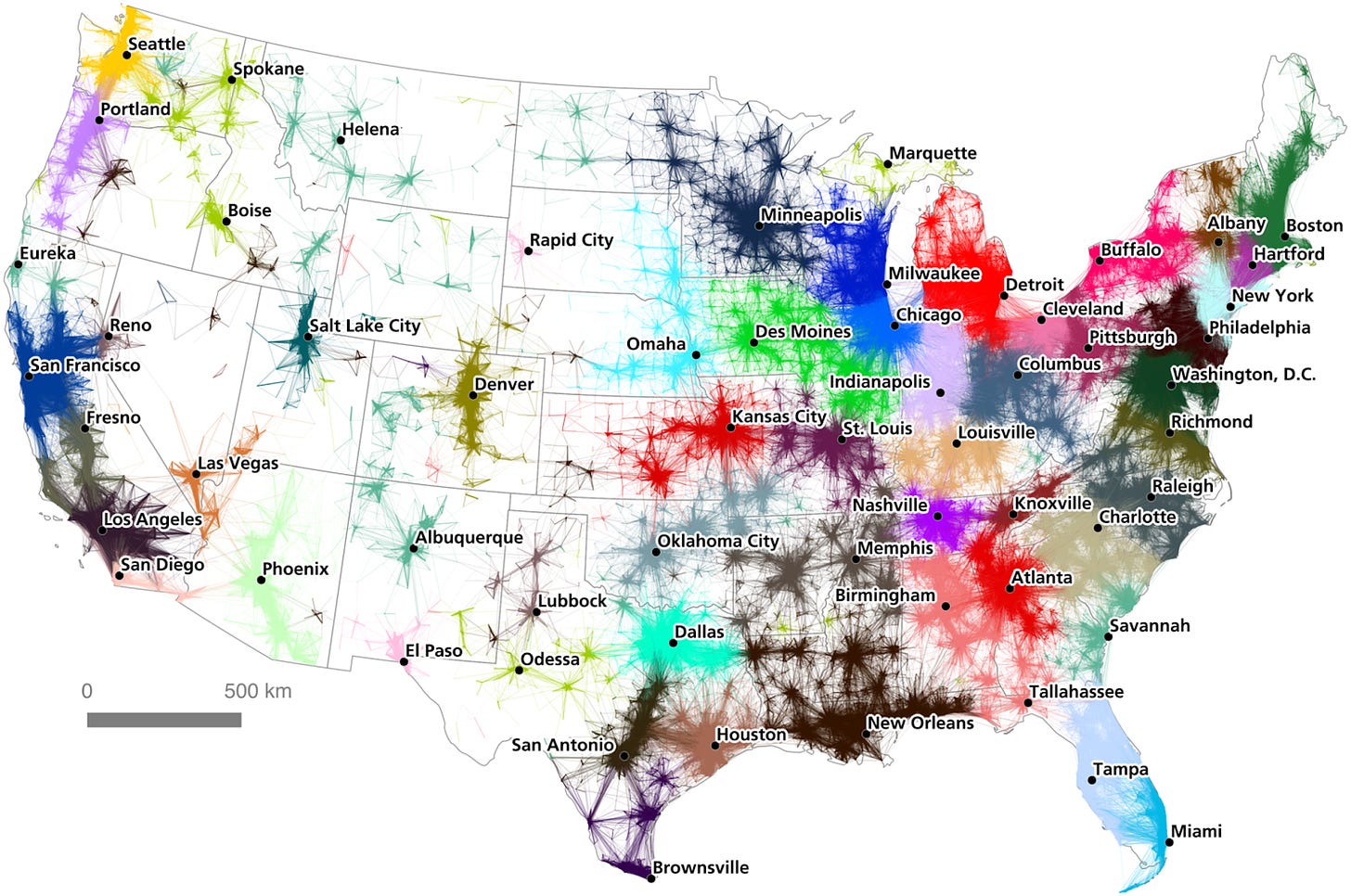

The economic geography of the US became composed of “megaregions” that surround an urban hub, traversing political and legal boundaries, with a constellation of smaller sub-centers interspersed throughout.

The commute became the fundamental unit of analysis in understanding the regional geography, population patterns, and capital and labor flows of the US.

But what happens when the commute becomes far less relevant for younger generations and the generations to come?

What happens if it becomes entirely irrelevant for the most creative, upwardly mobile, economically productive citizens of these generations?

One of the reasons I’m co-founding stuga.homes was our belief that remote work is a social and economic inflection point on par with the automobile.

I wanted to better understand what the new economic geography of the United States will look like in an age in which work has been decoupled from physical location. And in particular, we want to understand the likely impacts on housing and residential real estate markets.

To get started, I thought the answers to three questions would help.

First, how many jobs can be done remotely, and what types of workers are most likely to work remotely?

Second, what is the likely behavior of those workers and employers in an age of remote work?

Third, taking into account the answers to the first two questions, what’s the impact of remote work on housing markets?

The next three parts of this four part series will take each of these questions in turn.

Combining the answers to these three questions will allow us to begin to draw a picture of how the future economic geography of the United States might emerge in a new era of remote work and what it means for home prices, and for you.