Deficit Politics: The US Housing Deficit

We'll never "solve" the US budget deficit. But we can and should solve the US housing deficit.

The US budget deficit is the news again. You may have noticed.

Washington is second only to Hollywood in its willingness to sell us remakes - to tell us the same stories over and over again when they’re completely out of ideas but want to try to keep our attention.

So Washington’s back with another installment in one of it’s best known (and least liked) franchises—the debt limit showdown. Debt Limit 2023: Just Crazy Enough To Do It This Time?

Unfortunately for the audience, while Hollywood draws upon a deep well of storytelling genres they can entertain us with, Washington only has one in its repertoire: kayfabe.1

The statutory debt limit requires that the US Congress affirmatively pass legislation to enable total US government borrowings to exceed a statutorily-set, numeric threshold.2

If Congress doesn’t do its job and pass a bill that includes a provision to literally strike the number $31.4 trillion and replaces it with some larger number, bad things happen.

Namely, the US Treasury will default on its payment obligations, which will call into question the full faith and credit of the United States government, which will undermine confidence in the US dollar as global reserve currency, which will cause haywire in market for “risk free” interest rates upon which the entire global financial architecture has been built.

Or not? The main point is we probably don’t want to find out.

Anyways, this story is dull. And now there’s a bi-partisan budget deal, which looks likely to have the votes to pass. So it’s almost over…until they produce the next installment in this long-running comedy-horror series.

Let’s talk about a more interesting deficit story: the housing deficit. It’s too early to tell, but there’s a chance this one has a happy ending.

The US has a housing deficit. I define the housing deficit as the difference between the current and expected supply of homes and the current and expected demand for homes.

The impact of the US housing deficit is decreased home affordability: limited inventory and elevated home values (now including high mortgage rates!).

Millennials are the cohort most impacted by the US housing deficit, and Gen Z aren’t far behind them.

Overall housing affordability has deteriorated in the US. We can see that by just looking at overall home prices and overall income.

Since 2011, median US home prices are up around 100%.

Over the same period, US median incomes have risen about 36%.

That’s a good situation to be in for existing homeowners, but it’s a particularly awful one for younger and first-time homebuyers.

And there are a lot of younger and first-time homebuyers entering the market.

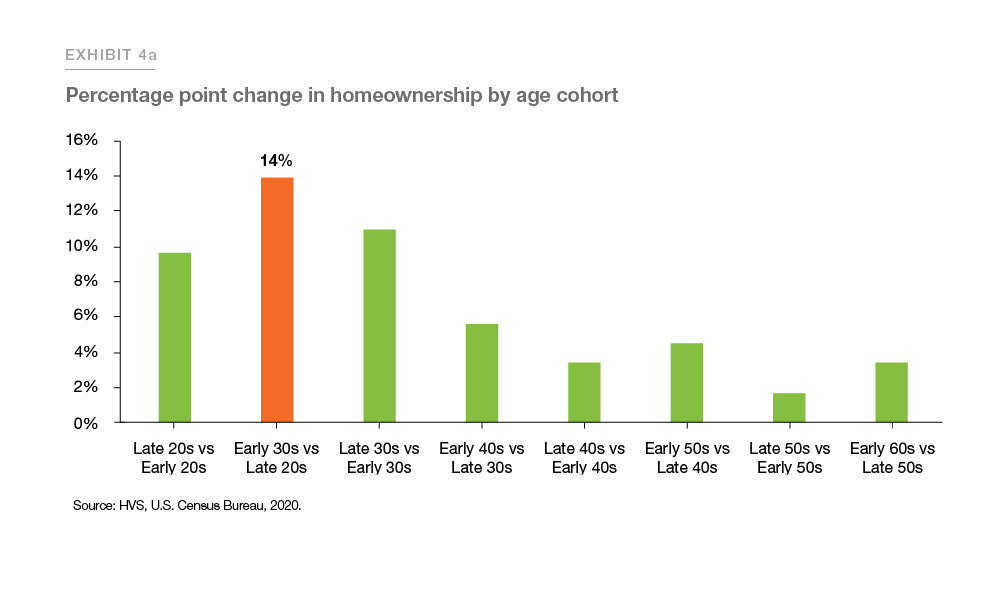

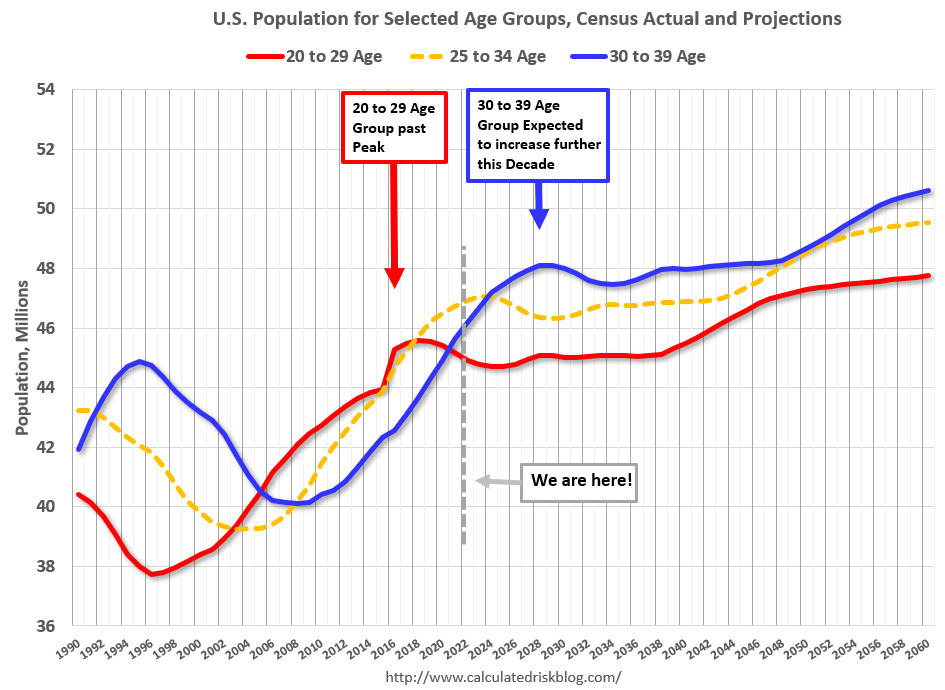

There are 72 million Millennials in the US. It’s a relatively large generation, and they’re entering the housing market en masse because they’re now becoming prime home-buying age consumers (30s-40s). We’re starting to see that in the Census data.

And demand from these age cohorts is going to remain elevated for the coming decade as the 30-39 age group (blue line below) is expected to increase this decade and then continue to increase in the subsequent decades.

So there’s a sustained wave of demographic-driven housing demand in the pipeline. Over the next 10 years or so, we’re probably looking at 10-13 million additional new homebuyers. The problem is that we don’t, and probably won’t, have enough homes for them. There are a few reasons why.

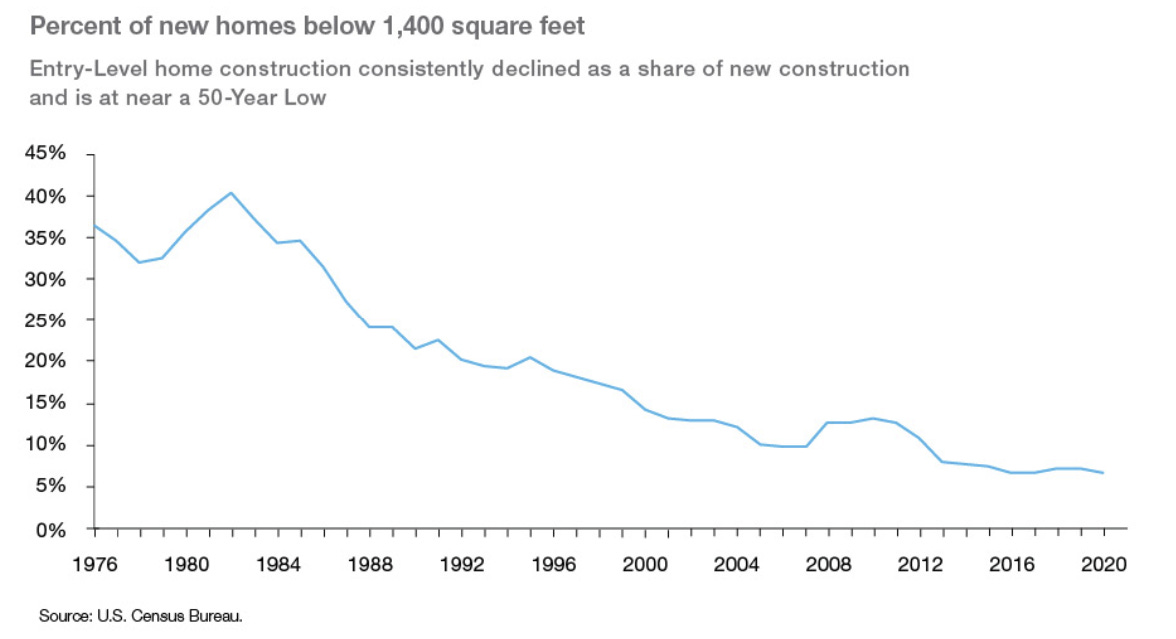

Starting in the 1970s, we slowly stopped building starter homes, defined as homes with less than 1,400 sq. ft.

In the 1970s, we were building an average of 400k+ entry-level homes per year accounting for 34% of all homes completed. During the 2010s, we completed an average of 55k entry-level homes per year accounting for only ~10% of homes completed.

We basically stopped building homes for the fastest-growing segment of the home-buying market.

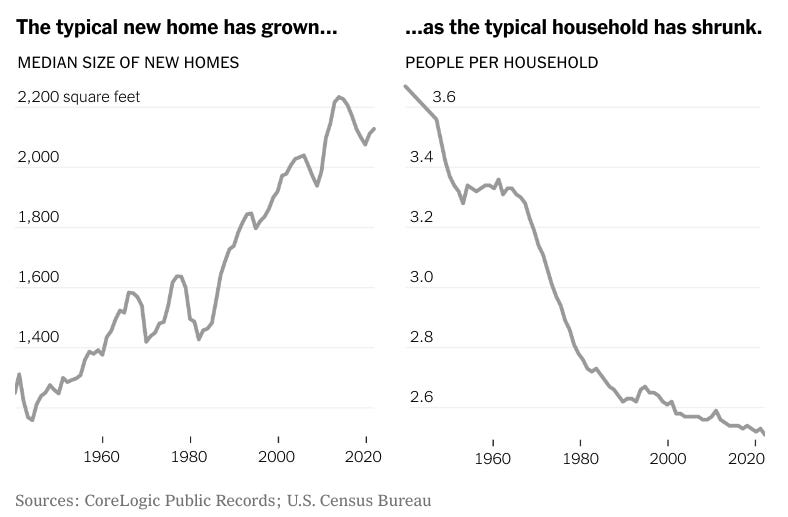

Instead, we’re building much larger homes, even as the typical American household size has fallen.

One of the primary reasons we’re building homes that are too big for the largest segment of the market is because of overly restrictive zoning laws. You simply cannot build a greater number of smaller homes in many places where people want to live, because that would increase housing density, and zoning laws have effectively outlawed that.

All told, the result is a housing deficit that’s estimated to be over 4 million homes.

And it’s unlikely that we’ll be able to build our way out of it, because productivity in the construction sector has collapsed.

Relatedly, one of the main drivers of our housing deficit is that we didn’t build enough homes after the global financial crisis. Just look at red line pre-and-post global financial crisis:

Why did this happen? Because after the housing collapse in 2007-08, the homebuilding industry was decimated, and tradesmen sought alternative employment in areas like law enforcement. So we didn’t have the capacity to build more then, and we don’t have the capacity we need to build more now.

Where do we go from here? The prospects for implementing solutions adequate to the challenge within a sufficient period of time are pretty low. It’d be foolish to expect that Washington is going to ride to the rescue any time soon. Our political and policymaking processes might be too degraded.

Even if DC could summon the will to focus on enacting meaningful housing policy, it’s questionable how much federal legislation could actually help since many of these issues are hyper-local.

In a world where housing demand outstrips housing supply and we have sustained challenges with regard to housing affordability, younger home-buyers will probably need to find creative ways to make homeownership work for them.

They’ll be doing this in an era where many workers have more flexibility than ever before as a result of remote/flexible work. And they’ll be doing this in an era where the nature of the US household is undergoing significant change as younger workers form a greater diversity of household types.

We’re on the cusp of a bottoms up transformation of housing in this country, driven new cohorts of homeowners developing new models of homeownership amidst historic levels of home unaffordability.

Who will build the tools they need to do this? I’ll have much more to say on this topic in the coming months.

I’ve been reliably informed that Kabuki, the long-preferred DC insider term for this song and dance, is no longer the preferred nomenclature. And anyway the intended meaning in this context from the use of Kabuki, or misuse as the case may be, is nearly synonymous with that of kayfabe.

Congress used to pass spending bills and include authorization for the Treasury to borrow whatever was needed to fund the priorities contained in each of those spending bills. But Congress got tired of doing that because the politics of doing so started getting dicey.