What the hell's going on in the housing market?

Why your housing market narrative is probably wrong.

The US housing market is a tough place to navigate right now.

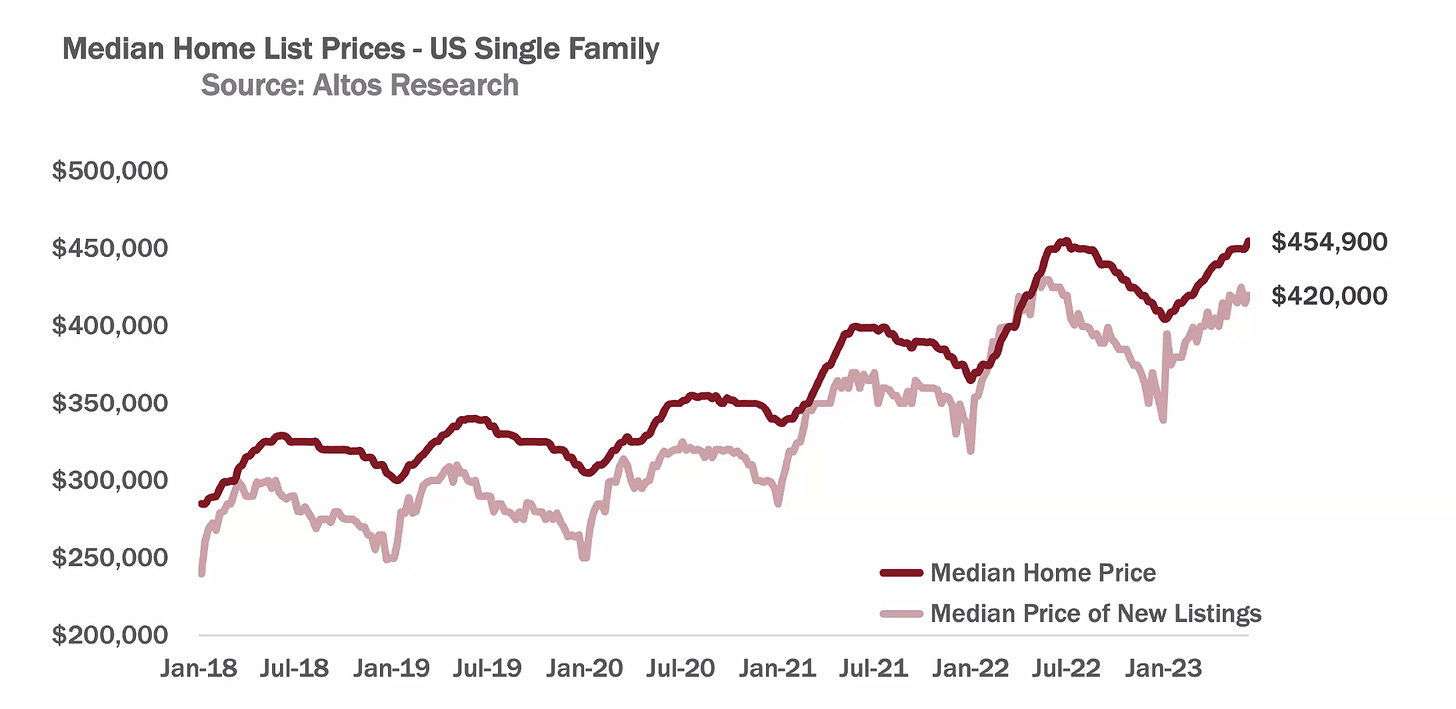

Many expected home prices to collapse after the Covid-era boom, which saw overall housing prices climb 40%+ in two years, was immediately followed by a spike in mortgage rates. Home prices not only haven’t collapsed but have continued to increase in many markets, especially those in the Midwest and East Coast.

The real estate industry is basically in a depression - decreased levels of sales activity, mass layoffs, business failures, etc. But amidst it all, US home values might end the year slightly up year-over-year.

It’s a brutal situation for everyone - except for existing homeowners (the Boomers win again!). It’s an especially brutal situation for first-time homebuyers.

What the hell is going on in the housing market?

My view, for what it’s worth, can be summarized in two sentences: Existing homeowners can’t afford to sell. And you can’t buy what’s not for sale.

Let’s take a closer look.

Homeowners Can’t Afford to Sell.

The fundamental problem with the housing market is that we are in a supply constrained environment.

The inventory of available homes for sale is about half of what it was before the pandemic. So far, the much hoped-for bounce in inventory hasn’t happened yet. And we’re likely on a path to hitting another all time low of housing inventory by the end of the year.

The reason that housing inventory is so low is that existing homeowners can’t afford to sell. What does that mean exactly?

Millions of Americans bought homes or refinanced into lower mortgage rates when rates were low. It’s estimated that between 25-30 million homeowners have mortgage rates of around 3% or lower. 62% of homeowners have a mortgage rate below 4%. Today, they’re hovering around 7%.

Higher mortgage rates have a hugely negative impact on home affordability. With a 3% mortgage, the monthly payment for a $600k house is $2,000/month. At 7%, it’s $3,800/month - nearly double.

So imagine you’re an existing homeowner with a <3% mortgage and you’re thinking about moving. At today’s mortgage rates you’ll only be able to afford a home about half of what your current home is valued at. Alternatively, you could pay about twice as much per month for a similarly valued home. It makes a lot of sense to stay put! As a result, inventory stays off the market.

You can’t buy what’s not for sale.

There’s a massive amount of pent up housing demand, so there are a lot of people out there that want to buy right now.

That’s why, even during a period where mortgage rates are higher than they’ve been in 20+ years, you’re still seeing viral social media posts like this one:

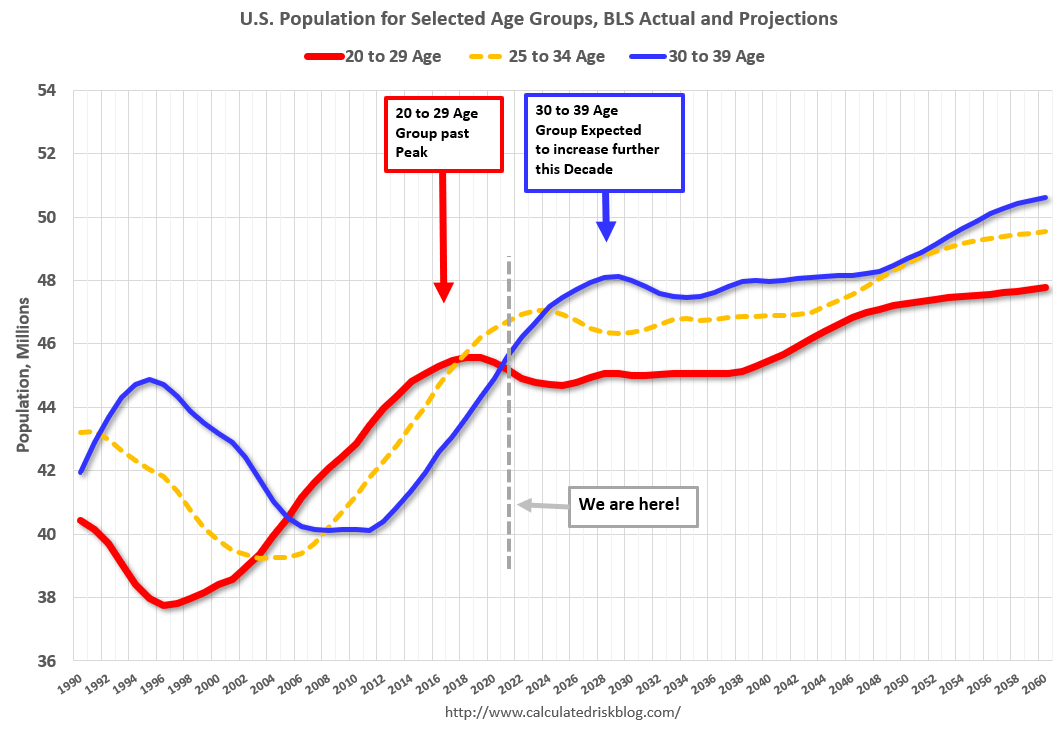

Housing demand is ultimately driven by demographics, and there’s a generational surge of housing demand underway as Millennials and Gen Z become prime home-buying age consumers (approx. 30-40 y.o.), which you can see in charts like this one:

All told, there’s a pool of about 10-15 million first-time homebuyers who will be hitting the market over the next 10 years. Expect to see healthy housing demand in the decade to come.

Why your housing market narrative is probably wrong.

Let’s have a look at two narratives I commonly see about the housing market that are probably wrong.

Narrative 1. You should wait for mortgage rates to come down so that housing will be more affordable.

Maybe? There are two main problems with this narrative.

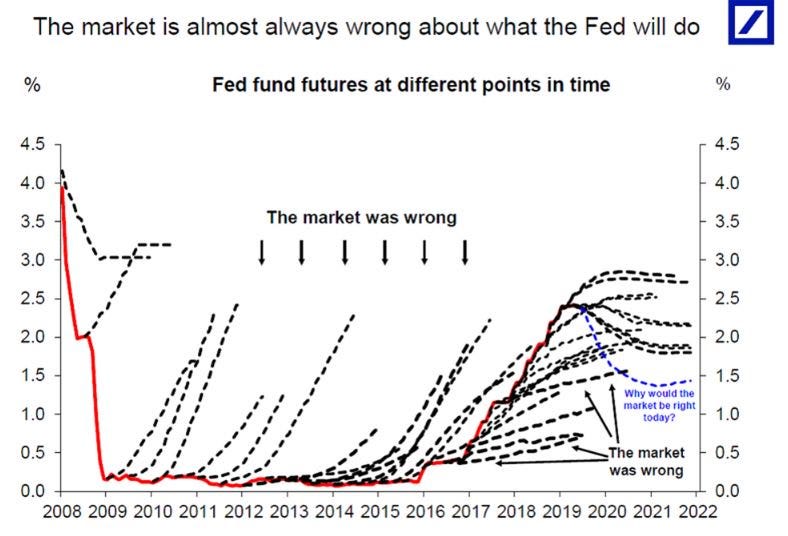

First, how do you know rates are going to come down? Interest rates are a complex interplay between economic conditions, Federal Reserve policy, and market expectations. There are thousands of highly trained professional investors and market makers who get paid a lot of money to get it right. Let’s have a look at how they do:

Turns out, accurately predicting the path of interest rates is…pretty hard! I think it’s fair to assess professional market participants’ ability to predict the path of interest rates as:

What makes you think you’re going to do any better?

There’s another problem with this narrative. Let’s assume that interest rates do come down. Guess what - everyone else who’s been waiting on the sidelines is going to jump back into the market. As we just discussed, there’s a lot of pent up demand out there, and we’re in a supply constrained environment.

That lower rate doesn’t help when you’re getting out-bid on a limited inventory of homes in a hot market.

Narrative 2. When rates go down, supply will come back onto the market, because existing homeowners won’t have to pay up as much for a mortgage on a new home.

In this narrative, lower rates lead to a reduction in the “mortgage rate lock-in effect.” The idea here is that as the gap narrows between available mortgage rates and the historically low mortgage rates people are locked into, they’ll feel less “stuck” in their existing home and will be more likely to put it on the market.

The main problem with this narrative is that it’s more likely the opposite is true. If mortgage rates fall, the historical data shows we’re actually going to see even less inventory than what we see out there today.

Why is that the case? Lower mortgage rates make the “carrying cost” of owning a home much lower - making it cheaper to own and to hold.

So if you’re an existing homeowner buying a new home, you might not need to sell your current home. At low rates, the combined carrying cost of both homes is so low that you can afford to hold both of them.

Additionally, homeowners now have access to a plethora of digital tools and services that make it easier than ever to become a landlord. So instead of selling your previous home, you might rent it out. And since your mortgage rate is so low on that property, doing so is likely to generate a nice income stream for you.

Conclusion

There’s another reason these narratives could be wrong. We could have a severe recession that wipes out employment and income and leads to defaults and distressed sales coupled with lower rates. Overall, this would be bad. But assuming you don’t also lose your job, this could create more inventory and lead to some bargains. Distressed sales don’t happen instantaneously though. They can take 18+ months from the point of a missed payment.

No one has a crystal ball. But right now the likeliest path we’re on is an multi-year period wherein rates stay higher for longer with a housing affordability crisis that grinds on as inventory slowly normalizes.

What can be done? In future posts, I’ll address opportunities for policy reforms and entrepreneurial innovations that can make a meaningful difference.